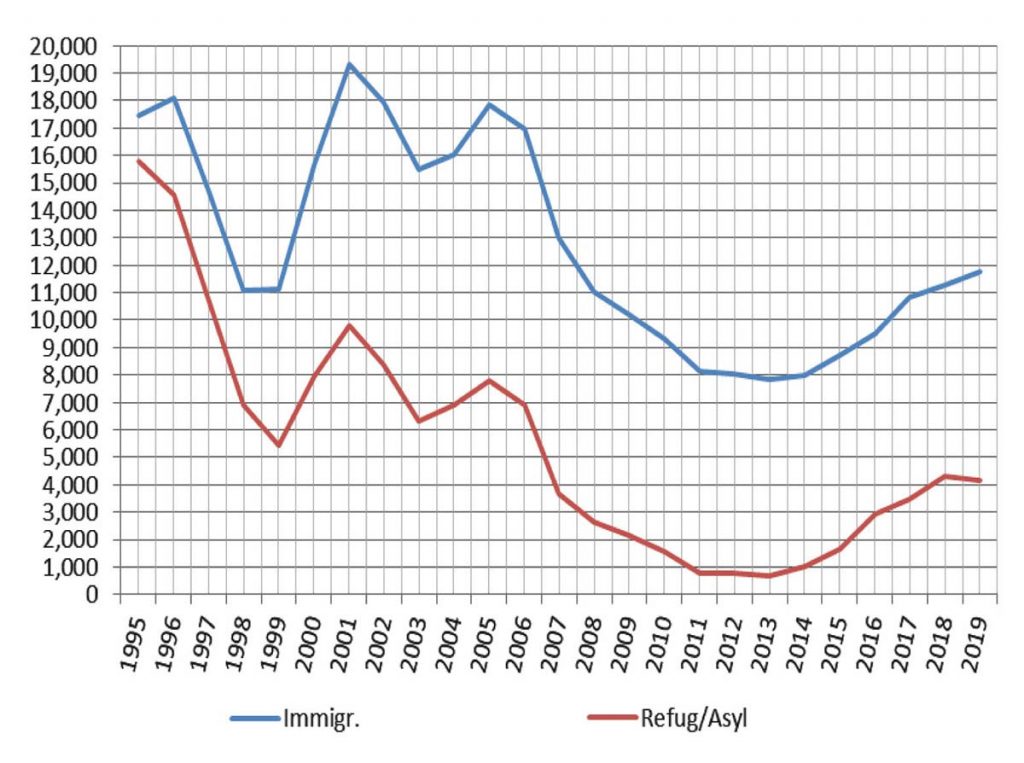

The annexation of Crimea and the invasion of eastern Ukraine by Russia in 2014 produced many consequences. One of them was the displacement of a large number of persons within the territory of Ukraine. This displacement created a severe internal refugee problem. The exact number of displaced persons is unknown, but estimates are in the...